Ever bought a generic pill and been shocked by the price-only to find your neighbor paid a third of that for the same medicine? It’s not a mistake. Generic drug prices vary wildly across U.S. states, sometimes by hundreds of percent, even for identical prescriptions. A 90-day supply of atorvastatin might cost $12 in Texas and $45 in California. In rural areas of Arizona, it could hit $80. This isn’t about brand names or patents-it’s about generics, the cheapest drugs on the market. So why do prices swing so wildly? The answer isn’t simple, but it’s rooted in state laws, middlemen, and a system designed to hide costs.

How PBMs Control What You Pay

Pharmacy Benefit Managers, or PBMs, are the hidden players in your prescription price. They negotiate deals between drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and insurers. But here’s the catch: they don’t always pass savings to you. In many states, PBMs set secret reimbursement rates that pharmacies must accept. If your insurance says your copay is $10, that doesn’t mean the pharmacy gets $10. Often, the pharmacy gets far less-sometimes less than the cost of the drug itself. To make up the difference, they charge you more out-of-pocket, especially if you’re paying cash.Research from the USC Schaeffer Center found that U.S. consumers overpay for generics by 13% to 20% because of how PBMs structure contracts. In states with little oversight-like Mississippi or Alabama-these practices are more common. In contrast, states like California and Vermont require PBMs to disclose their pricing formulas. That transparency leads to lower prices. One study showed patients in states with strong transparency laws paid 8-12% less for generics than those in states without them.

Medicaid and Reimbursement Formulas

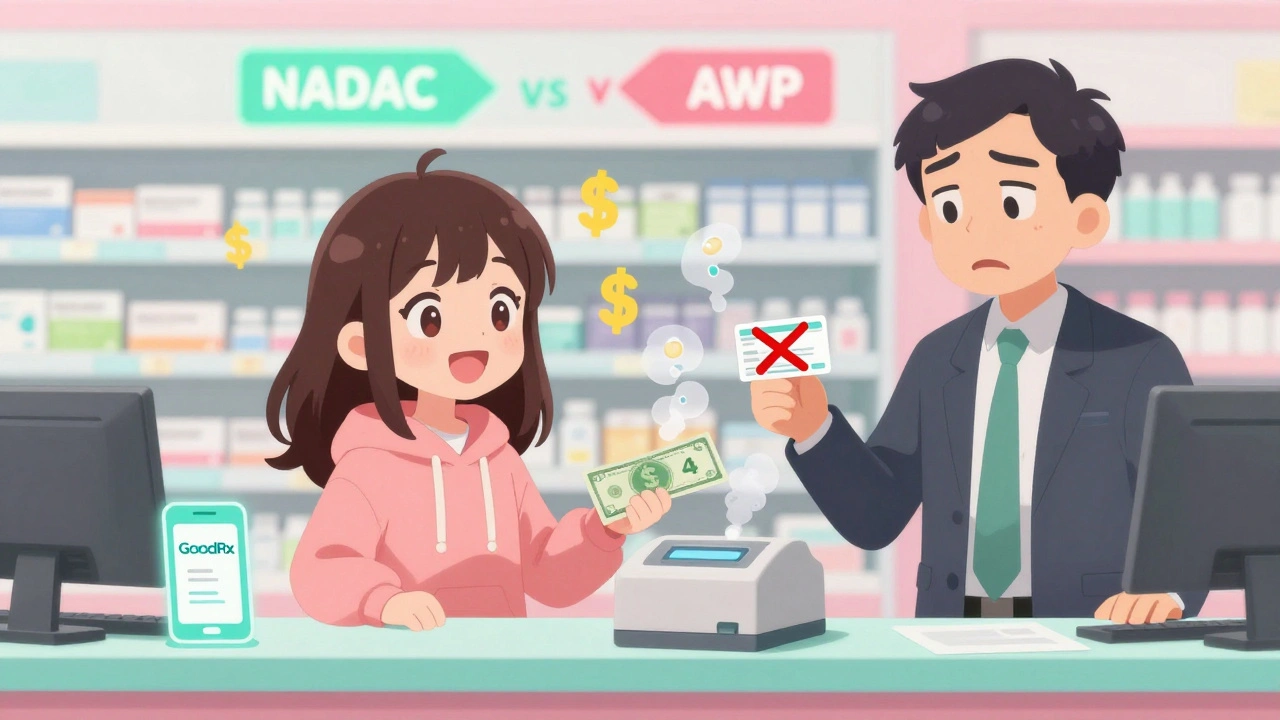

Medicaid, which covers millions of low-income Americans, sets the baseline for many private insurers. But each state runs its own Medicaid program-and each uses a different method to calculate how much it pays for generic drugs. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), updated monthly. Others use older benchmarks like Average Wholesale Price (AWP), which is often inflated and outdated.States using NADAC tend to pay closer to what pharmacies actually pay for drugs. States clinging to AWP? They overpay-and that overpayment gets passed down to you. If Medicaid pays more, private insurers often follow suit. So if your state’s Medicaid program pays $1.20 for a bottle of generic lisinopril, your insurer might set your copay at $5. But in a state where Medicaid pays only $0.80, your copay might be $3. The drug is the same. The cost to the system is different. And you’re the one paying the difference.

Competition (Or Lack of It)

In cities with dozens of pharmacies, competition drives prices down. In rural towns, you might have one or two options. That’s not just inconvenient-it’s expensive. A 2022 GoodRx analysis found that in areas with fewer than three pharmacies, generic drug prices were 30-50% higher than in urban centers. Why? Less competition means less pressure to lower prices. And without price transparency laws, pharmacies don’t have to tell you what they’re charging.This is why cash-only pharmacies like Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company and Blueberry Pharmacy are growing. They cut out the PBM middleman entirely. You pay a transparent markup-often 15-20% above what the pharmacy paid for the drug. No hidden fees. No surprise bills. In states with weak regulation, these cash pharmacies are often the only way to get fair prices. A patient in Ohio paying cash for metformin might spend $4 for a 90-day supply. The same drug under insurance? $45.

State Laws Try to Fix the System-But Hit Legal Walls

In recent years, states tried to step in. Maryland passed a law in 2017 to stop “price gouging” on generic drugs. Nevada targeted diabetes meds. California required drug makers to report price hikes. But in 2018, a federal court struck down Maryland’s law, saying states can’t regulate prices that cross state lines. That ruling sent a chill through state legislatures. Other lawsuits, like Nevada’s, were dropped-not because they were weak, but because manufacturers threatened to sue under trade secrets laws to block price data from being released.Today, 18 states have created drug affordability review boards. These boards can investigate price spikes and recommend action. But they can’t force manufacturers or PBMs to lower prices. They can only say, “This looks unfair.” That’s not enforcement. It’s a warning. Meanwhile, federal law still doesn’t cap generic prices. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped insulin at $35 for Medicare patients and will cap out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000 a year starting in 2025. But those rules only apply to Medicare. That’s 32% of drug spending. The other 68%? Still at the mercy of state-by-state chaos.

Why Paying Cash Often Beats Insurance

It sounds backwards, but for generics, paying cash is often cheaper than using insurance. Why? Because your insurance plan doesn’t pay the pharmacy the full price. It pays a negotiated rate that’s usually lower than what the pharmacy paid for the drug. So the pharmacy makes you pay the difference. That’s your copay. But if you pay cash, you’re paying the pharmacy’s actual cost plus a small markup-no middleman, no hidden fees.Here’s the data: 4% of all U.S. prescriptions were paid in cash in 2020. Of those, 97% were for generics. That’s not a coincidence. People figured it out. GoodRx found that cash prices for generics were 30-70% lower than insurance prices in most states. In some cases, like in Georgia or Kansas, the cash price was under $5 for a 30-day supply of generic sertraline. With insurance? $40.

The trick? Always ask: “What’s your cash price?” before using insurance. Many pharmacies will give you a lower price if you pay upfront. You don’t need a coupon. You just need to ask.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for Congress or your state legislature to fix this. Here’s how to save money today:- Use GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices at nearby pharmacies. Enter your drug, dose, and zip code. The lowest price will show up first.

- Ask your pharmacist: “What’s your cash price?” Don’t assume insurance is cheaper.

- If you’re on Medicare, check if your drug is covered under the $35 insulin cap or the new $2,000 out-of-pocket limit. Even if you’re not on Medicare, some pharmacies honor those caps for non-Medicare patients.

- Consider mail-order pharmacies or cash-only services like Cost Plus Drug Company if you take long-term meds. Shipping is often free, and prices are fixed.

- In states with transparency laws (California, Nevada, Maine, Vermont, Maryland), use their online drug price databases to track trends. You can even report suspicious price hikes.

The Bigger Picture

The U.S. pays 2.78 times more for prescription drugs than other wealthy countries. That’s not just because of brand-name drugs. It’s because of how generics are priced. The system is broken-not because manufacturers are greedy, but because middlemen have built a maze of contracts, rebates, and secret fees that nobody outside the industry understands. And state lines have become borders between fair pricing and exploitation.But here’s the good news: you have power. You don’t have to accept whatever price you’re given. You can compare. You can pay cash. You can ask questions. And as more people do, the system will have to change.

Why is my generic drug more expensive in my state than in others?

Generic drug prices vary by state because of differences in Medicaid reimbursement formulas, Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) contracts, pharmacy competition, and state transparency laws. States like California require PBMs to disclose pricing, leading to lower costs. In states with no such laws, PBMs can set secret rates that inflate your out-of-pocket price-even if your insurance says you’re paying a low copay.

Should I always use my insurance for generic prescriptions?

No. For generics, paying cash is often cheaper than using insurance. Insurance plans don’t always pay pharmacies enough to cover the drug’s cost, so pharmacies charge you the difference. Cash prices through services like GoodRx or Cost Plus Drug Company can be 30-70% lower. Always ask your pharmacist for the cash price before using insurance.

Are there states where generic drugs are consistently cheaper?

Yes. States with strong transparency laws-like California, Vermont, Maine, and Nevada-tend to have lower generic prices. These states require PBMs and drug makers to report pricing data, which reduces hidden markups. Rural areas in any state usually have higher prices due to fewer pharmacies and less competition.

Can I get generic drugs cheaper by buying them online?

Yes-if you use trusted, licensed online pharmacies. Services like Cost Plus Drug Company, Blink Health, and GoodRx Mail offer transparent pricing and ship directly to your door. Prices are often lower than local pharmacies because they cut out PBM middlemen. Avoid unlicensed websites; they may sell counterfeit or expired drugs.

Does the Inflation Reduction Act help with generic drug prices?

Only for Medicare beneficiaries. The law caps insulin at $35/month and out-of-pocket drug costs at $2,000/year starting in 2025-but only for people on Medicare. It doesn’t directly control generic prices for privately insured or uninsured patients. However, it may pressure PBMs to lower prices over time as Medicare’s bargaining power grows.

Ignacio Pacheco

December 3, 2025 AT 07:00So let me get this straight-we pay more for the exact same pill depending on which state we live in, and the reason is some middleman hiding behind a spreadsheet? I’m not mad, I’m just disappointed.

Also, why does my pharmacy charge me $40 for metformin when I could buy it for $5 cash? Did I miss the memo where insurance became a charity program for PBMs?

Gavin Boyne

December 4, 2025 AT 13:25It’s not broken-it’s by design. The entire system is a Rube Goldberg machine built to extract money from sick people while pretending to help them.

Think about it: PBMs don’t care if you get your medicine. They care if they get their cut. And states? They’re either asleep or bought out. California’s transparency laws work because people fought for them. In Alabama? You’re just a data point in a profit model.

The real tragedy? The drugs themselves cost pennies. The system is the disease. And we’re all patients in it.

Next time you pay $50 for a generic, ask yourself: who really got rich off this transaction? Hint: it wasn’t the pharmacist.

Rashi Taliyan

December 4, 2025 AT 14:33I come from India, where a month’s supply of metformin costs less than $1-and yes, it’s the same generic.

Here in the U.S., I’ve seen friends cry over pharmacy bills. It’s not healthcare. It’s extortion with a prescription pad.

When I told my cousin back home about this, she laughed and said, ‘In our village, the pharmacy gives you the medicine and asks for your name. That’s it.’

I don’t know whether to laugh or cry.

Kara Bysterbusch

December 4, 2025 AT 22:45Let’s be clear: the American pharmaceutical-industrial complex is a masterclass in performative capitalism.

It’s not just about PBMs-it’s about the entire architecture of healthcare being optimized for shareholder value, not human survival.

Imagine a world where your insulin isn’t priced based on how much you’re willing to beg, but on how much it costs to synthesize.

That world exists-in Canada, in Germany, in India. But here? We’ve turned medicine into a luxury good with a side of moral panic.

And yet, somehow, we still act surprised when people skip doses.

It’s not negligence. It’s rational survival.

Rashmin Patel

December 6, 2025 AT 19:49OMG I JUST REALIZED WHY MY COUSIN IN TEXAS PAID $8 FOR ATORVASTATIN AND I PAID $42 IN NEW YORK 😭

It’s not even about the drug-it’s about the SYSTEM. PBMs are like the mafia but with Excel sheets and fancy titles.

And guess what? I started using GoodRx last month and saved $180 on my meds. I didn’t even need insurance. I just asked. That’s it.

Also, if you’re paying cash and your pharmacy gives you side-eye? Tell them you’re not paying for their corporate overhead. You’re paying for the pill. Period.

PS: I just sent my mom to Cost Plus Drug Co. She’s now on a 90-day supply of lisinopril for $7.50. She thinks she won the lottery. She didn’t. She just learned how to game the broken system.

WE CAN DO THIS. BUT WE HAVE TO TALK ABOUT IT.

❤️❤️❤️

sagar bhute

December 8, 2025 AT 15:30Cindy Lopez

December 9, 2025 AT 20:10There is a grammatical error in the third paragraph: 'They negotiate deals between drug manufacturers, pharmacies, and insurers. But here’s the catch: they don’t always pass savings to you.' The pronoun 'they' is ambiguous. It should specify 'PBMs.'

Also, 'NADAC' is capitalized correctly, but 'AWP' should be preceded by 'the' for consistency.

Otherwise, the content is accurate, but the formatting lacks paragraph cohesion.

shalini vaishnav

December 11, 2025 AT 04:31India has cheap generics because we don’t have patent laws. We copy everything. That’s not innovation. That’s theft.

Meanwhile, the U.S. spends billions developing life-saving drugs, and now you want us to give them away for free? You don’t get to have both.

Stop complaining. Go to India if you want cheap pills. We didn’t invent the problem-you just don’t like the solution.

vinoth kumar

December 12, 2025 AT 18:00Just wanted to say thank you for this post. I’ve been paying cash for my meds for two years now after learning about GoodRx.

My wife and I used to spend $200/month on generics. Now? $45. We used to think insurance was helping us. Turns out, it was just the middleman’s vacation fund.

My mom didn’t believe me until I showed her the receipts. Now she uses it too.

If you’re reading this and you’re paying over $10 for a generic without checking cash prices-you’re leaving money on the table.

Just ask. It’s that simple.

bobby chandra

December 13, 2025 AT 06:44Let me paint you a picture: You’re a pharmacist in rural Ohio. You pay $1.10 for a bottle of generic sertraline. Your insurance reimbursement? $0.90. So you charge the patient $40 to cover rent, staff, electricity, and the fact that you’ve been working 12-hour days since 2019.

Meanwhile, the PBM pockets $25 of that $40 and calls it a ‘rebate.’

This isn’t capitalism. It’s a circus where the clowns are accountants.

And yet, somehow, we’re supposed to be grateful that we can even get the damn pills?

Wake up. The system is rigged. But guess what? You’re not powerless. Ask for cash prices. Use GoodRx. Call your state rep. Stop being quiet.

Archie singh

December 14, 2025 AT 01:38Gene Linetsky

December 15, 2025 AT 12:17Did you know the same companies that make these generics also own the PBMs? And the PBMs own the pharmacies? And the insurance companies are owned by the same billionaires?

This isn’t a coincidence. It’s a monopoly. They’re not just hiding prices-they’re hiding ownership.

They want you to think it’s about states or laws. Nah. It’s about control.

Next time you see a $50 generic, remember: that’s not a price. That’s a tax on your illness.

And they’re laughing all the way to the Caymans.

Vincent Soldja

December 16, 2025 AT 06:25Myson Jones

December 17, 2025 AT 10:39Thank you for writing this. I’ve been struggling with my blood pressure meds for years and never realized I could pay cash and save half.

I’m not a policy expert, but I know what it feels like to choose between food and medicine.

If you’re reading this and you’re scared to ask for the cash price-please, just do it. The pharmacist isn’t judging you. The system is.

You’re not alone. And you’re not broken. The system is.

parth pandya

December 19, 2025 AT 04:09OMG i just found out about goodrx and i saved 70$ on my antidepreshin last month!!

my pharimacist was like oh yeah we can do that if you pay cash

i had no idea!!

so now i check every time i get a script

also i told my aunt and she cried she was payin 80$ for lisinopril

now she pays 6

pls tell everyone

its not rocket science

just ask